My last blog was about C-section scar massage: why it’s beneficial and how to do it.

And so many of you told me how useful it was, as there is so little information given to C-section mamas about their scars and how it can affect them.

But quite a few of you also commented that you can’t touch (or in one case even look at) your scar. When I did my postnatal massage course and we did scar massage this was discussed, but I have to admit it’s not something I’ve come across much, so it isn’t my area of expertise.

So I’ve called on 2 wonderful therapist friends to shed some light on this.

Rachel Weber of Time and Space Therapies is a massage therpist and ex-midwife who also runs Birth Story Workshops and 1:1 sessions, and Kate Codrington is also a massage therapist, and runs self-help Love Your Belly Workshops.

None of my massage clients have had this issue, but I’m aware of it from my training. How common do you find it?

Kate: I’ve come across it a handful of times in my work with pregnant women, all of those were emergency sections where there are unresolved feelings about the birth. Of course when a woman has been given time to prepare for a section it is much less common.

Rachel: I come across this fairly often, women who can’t look at or think about their scar even years after. Sometimes they have NEVER looked at their scar. They don’t think anything of it, they just think it’s normal not to.

This can be a very emotional issue can’t it, in relation to birth trauma?

Rachel: For a lot of women the scar is a constant reminder of the birth they didn’t want and of any trauma surrounding that. It is likely to be holding deeper issues as well that they are not necessarily aware of on a conscious level; feelings of having failed, of their body having failed them, even of being a ‘bad’ mum or of being weak, not speaking up for themselves, or deep hurt about how they had been treated or not listened to etc.

These feelings can be very hard to acknowledge and society/family often don’t know how to deal with them and expect us to be ‘grateful’ so we tend to cover them up to the point of not even knowing they are there.

Kate: Exactly! Then this hurt can be projected onto the mother’s body and in the case of scar aversion, the scar itself.

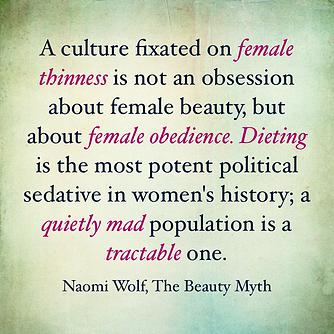

Once baby has arrived, our energy needs to come back in; our boundaries re-form into a new identity. A mum; we become mum-shaped! But women need a safe, nurturing environment for this to happen in. Expectations are set off kilter by media images of celebrity mums, which force women into diet and fitness regimes that are not nourishing for new mums and will actively delay recovery. We seem to have lost the practice of protecting and nourishing new mothers with massage and special food and practices in mainstream culture.

So do you find similar with women after vaginal births too?

Rachel: Women hold onto a lot of emotion around their births in general, and this can be for all different reasons. A lot of women have also never looked at their perineal scars/stitches, often because they are ‘scared’ of what they will find. Some even get their husbands to do it for them but have never looked themselves.

Kate: Yes, I regard scar aversion as being on a spectrum of distress following a birth that was traumatic in some way; for one woman it might show up as the desire to ‘get rid of’ her baby belly, or in a more extreme version, may not want to be touched or seen or be able to leave the house at all.

And as Rachel has said, women are so often told ‘well your baby is alive and well, be grateful for that!’ which can leave them feeling angry and embittered for years if the birth story isn’t processed. This can also affect their sense of self and attitude to their body too, that it’s let her down or is inadequate.

How do you help your clients overcome these issues?

Kate: In general I encourage women to have their feelings; they have a right to feel OK about being angry or betrayed or whatever. It’s helpful if these feelings are expressed in a safe place;

- Writing in out

- Drawing it

- Telling the story with safe people who will hear her without judgement. Rachel’s Birth Story Listening group is a wonderful place to start.

Yes, Rachel I imagine your role as a midwife as well as a therapist is valuable in helping women process their birth experiences? Where do you start?

Rachel: First I help her to acknowledge how she really feels about what happened. This can be more difficult and emotive than it sounds as she may never have admitted these feelings before. She can talk to someone or write it down. In relation to her scar she can write a letter entitled ‘Dear Scar.’ This is likely to reveal things she had never thought about before. It may bring up anger in which case it’s important to release it as suppressed anger can cause depression. She can yell in the car or under water, bash a pillow or do some vigorous exercise. In my sessions I would also help people explore the deeper beliefs they have formed about themselves; I am helpless, I am weak, I am a failure etc. and clear these using mind-body techniques.

And what about massage itself- obviously we don’t have to work directly on the scar, and won’t if the woman can’t touch it herself, but massage goes beyond muscular release.

Kate: I use a combination of visualisation and off-body work to help women heal scars. If they enjoy it I encourage them to do the same process at home. This can include;

- Placing my hands above and below the scar, either on or off the body according to what feels most comforting for the woman, and visualising the energy as light passing from one hand to the other, through the scar.

- Visualising the muscle and skin fibres knitting together.

- Sending a river of love from the heart to the pelvic basin to sooth and heal the scar and the remaining trauma, washing it away into the ground.

The energetic focus of postnatal massage is to bring the energy back in so the woman can heal and ‘come back to herself’. To do this I use a focussed intention as I massage the aches and pains and also by wrapping with rebozo shawls to ‘close the bones’, which symbolises the completion of the cycle of pregnancy and birth. I usually combine it with belly massage that also encourages the womb and intestines back into their place, bringing more energy and vibrancy back and encouraging the rectus muscles to return to the midline.

How important a part of the recovery process/ self-love journey do you think this is?

Rachel: I think it’s very exhausting to have suppressed emotion, and the scar and being able to look at it or not forms part of this equation. At the same time it can take a lot of courage to face these issues and it may be years before someone is ready. People may also be in denial that it’s an issue. Having said that, most people are surprised how easy it can be to heal their emotions – often it can be as simple as expressing them – and wish they had done it sooner.

What changes do you see in clients who manage to overcome these issues/ this aversion?

Rachel: For me not wanting to look at one’s scar is part of a bigger picture of suppressed emotions. People say to me things like ‘this is the first time I’ve ever cried about this’ or ‘I didn’t realise I was holding so much.’ Obviously as you shed the emotions you free up space for more energy and more joy. In particular I find people become more present and more able to deal with stress without having emotional or angry outbursts (generally these outbursts are just stuff they have been carrying for a long time).

Kate: And touch helps us to reclaim and understand our bodies brining us back to ourselves so that we can feel gratitude for having created this amazing new being. After all, making a human is a neat trick!

Guest Post Bios

Kate Codrington

I wear 3 hats; I run online courses for therapists [http://www.katecodrington.co.uk/] who want to expand their practice, I am also a massage therapist [http://www.katecodringtonmassage.co.uk/] specialising in women’s health in my private practice in Watford and teach women self-help skills at Love Your Belly [http://www.loveyourbelly.org.uk/] workshops.

Rachel Weber

I help women heal emotionally from an upsetting, unexpected, confusing or traumatic birth so that they feel confident about life and childbirth again. I also do holistic and pregnancy massage and reiki. Based in Pitstone, healing sessions are also offered globally via Skype [http://www.timeandspacetherapies.co.uk/].